Hakurakuten Yama: The float of success and academic achievement

The Hakurakuten float depicts a scene in which the Tang poet Hakurakuten questions the Zen master Dōrin, who lives atop an old pine tree.

Hakurakuten, dressed in white garments and a traditional Tang cap and holding a shaku (flat ritual baton) in both hands, stands listening to Dōrin’s answer. Dōrin, wearing the purple robes and indigo hat of a high-ranking priest and holding a rosary and a priest’s staff, sits atop the tree.

When Hakurakuten asks him to explain the essentials of Buddhism, Dōrin replies, ‘Doing good and refraining from doing evil’; Hakurakuten says, ‘Even a child knows that much’. Dōrin explains, ‘Exactly – but isn’t it difficult even for a venerable old man of eighty to put that into practice?’ and Hakurakuten is full of admiration.

This float is thought to share Hakurakuten’s enlightenment and his truth-seeking spirit, and to be imbued with blessings for academic achievement.

Gion Matsuri: the world’s longest-running festival

Gion Matsuri is an annual festival in which Susanoo-no-Mikoto (the god of Yasaka Shrine) and his family are paraded through the worshippers’ town on three portable shrines. This has continued for over 1,100 years, making it the world’s oldest festival tradition. Gion Matsuri consists of two events: the Shinto ritual of mikoshi togyo* (parading portable shrines) performed by the officials of Yasaka Shrine, and the yamaboko junkō (parade of decorated floats) performed by the local leaders of Shimogyō Ward. It begins on 1st July with the kippu-iri** ceremony in each district which possesses a float; people welcome the gods on the 17th with the sakimatsuri (early festival) procession, and send them on their way with the atomatsuri (later festival) on the 24th. For three days preceding both the sakimatsuri and the atomatsuri, a yoiyama*** is held; the lanterns on each float are lit, and Gion festival music can be heard. On the 31st, Gion Matsuri comes to an end with the summer purification festival held at Eki Shrine in the Yasaka Shrine complex.

* togyo – bringing forth the portable shrines

** kippu-iri – the beginning of the rituals

*** yoiyama – a smaller festival held on the eve of the main festival

Local leaders’ hopes for an end to the epidemic

In 869, an epidemic swept the capital. Fearing that ‘the epidemic [was] the work of a vengeful ghost’, the Imperial Court held a goryōe* in order to appease it. The ceremony took place on the banks of the pond in the Shinsen-en, which lay to the south of the daidairi**. At this time, in order to pray for an end to the epidemic, the men of the city sent three portable shrines from Gion Shrine (as Yasaka Shrine was then known) to Shinsen-en, and constructed 66 floats, one for each of the provinces in the country at the time. This is said to be the origin of Gion Matsuri. After that, although Kyoto suffered disaster in the form of the Ōnin War and three large-scale Edo period fires, it was rebuilt each time. Gion Matsuri was interrupted during the Pacific War, but reinstated irregularly in Shōwa 22 and 23 (1947 and 1948). In Shōwa 27 (1952), the parade was revived in its pre-war form. From the Shōwa 30s (1955 – 1965) onwards, some changes were made due to traffic conditions and other issues; the route of the parade was altered, and the sakimatsuri and atomatsuri were combined into one. But in Heisei 26 (2014), the atomatsuri was revived for the first time in 49 years.

* goryōe – a ritual for the repose of souls, held to protect against curses

** daidairi – the Heian palace

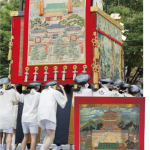

The ‘moving museum’ float parade

The floats which add magnificent flair to Gion Matsuri can be divided broadly into three categories: hoko, yama and kasaboko. Hoko are large, roofed structures centred on a shingi (pole made of yew plum pine, intended to draw the plague to it) and pulled by a cart. Kasaboko are elegant, two-storied umbrella-like structures adorned with decorations and pine. Yama can be separated into hikiyama and kakiyama. Hikiyama differ from hoko only in that the yew plum pine pole of the hoko is exchanged for a decorated pine. Kakiyama are, as it were, moving theatre stages, depicting a scene from myth, legend or folklore. The Hakurakuten float is a kakiyama; its decorated pine is the tallest in Gion Matsuri, reaching a height of more than 7m from the ground.

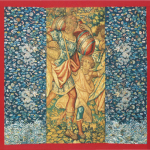

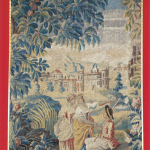

The many precious woven and dyed textiles from all over the world which decorate the floats are called kesōhin. They are magnificent, first-class works of art which entered Japan from overseas during the Edo period, hundreds of years ago. For this reason, Gion Matsuri is also known as the ‘moving museum’. The central tapestry of the frontal hangings decorating the Hakurakuten float was made in Belgium in the 16th century and depicts the fall of Troy, a scene from the Iliad.

Iliad: an epic poem written and passed down by Homer; it is famous for the Trojan horse.

A note on chimaki

Chimaki, which are made out of bamboo leaves, are charms against epidemics and disasters. They are associated with the dialogue between the poet Hakurakuten and the monk Dōrin, and amulets for academic success and for warding off misfortune and attracting good luck are attached to them.